Saturday, 31 March 2012

Collective Responsibility

Ultimately, the enforcement of the doctrine of ‘Collective Responsibility’ is down to the Prime Minister.

As the current version of the Ministerial Code states “Decisions reached by the Cabinet or Ministerial Committees are binding on all members of the Government.”

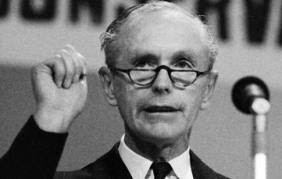

Harold Wilson, in his book describing his last period in office as Prime Minister (March 1974- March 1976), “Final Term” describes the problems he faced over ‘collective responsibility’.

“At a meeting of a sub-committee of the National Executive Committee [the Governing body of the Labour Party] in May [1974] three ministers dissociated themselves from Government policy by voting for a critical motion about [Chilean ships]…The problem was to come up again just after the October [1974] General Election, when three ministers voted in favour of a National Executive resolution criticizing the Government over a routine naval visit to Simonstown.”

Wilson wrote to the three offending Ministers – Tony Benn; Judith Hart and Joan Lestor:-

“Your vote in support of the Simonstown resolution at yesterday’s meeting of the National Executive Committee was clearly inconsistent with the principle of collective responsibility…..I must ask you to send me in reply to this minute an unqualified assurance that you accept the principle of collective responsibility and that you will from now on comply with its requirements and the rules that follow from it, in the National Executive Committee and in all other circumstances. I must warn you that I should have to regard your failure to give me such an assurance, or any subsequent breach of it, as a decision on your part that you did not wish to continue as a member of this administration.”

Location:

Milton Keynes, UK

Friday, 30 March 2012

Writing Constitutions

Having just finished marking the first eTMA on the Open University’s W201 course, I’ve read the phrase “unwritten constitution” many, many times in the last few days. It’s one of the key characheristics of the UK Constitution – but the term only appears in the second half of the Nineteenth Century. The first occurrence in Hansard (the almost verbatim report of what was said in Parliament) is in the 1850s, and it is rare until the 1870s. It was then that the idea of an unwritten constitution became popular (Bagehot has a lot to answer for!)

This was one of the nuggets contained in the lecture “Liberties and Empires: Writing Constitutions in the Atlantic World 1776-1848” given by Professor Linda Colley. She highlighted how popular writing constitutions had become after the Americans and French had excited peoples’ interest. London, a popular destination for political exiles from around the world, saw an incredible exchange of ideas.

Professor Colley is currently writing a book on the subject. She’s a historian – but her lecture was full of interest for those with an interest in Constitutions – and as I come to the subject as an academic in both the legal and political science fields, I found it fascinating. She described the work of people like John Cartwright and Jeremy Bentham, and traced the interest in the Magna Carta. There was an explosion in constitution writing as the idea spread that Government could be “simple, accountable and broadly based”. Perhaps it’s time for us in Britain to return to those interests of the late 18th and early 19th Century?

Labels:

Constitutional Law,

Hansard,

Jeremy Bentham,

John Cartwright,

Linda Colley,

Magna Carta,

Open University,

W201

Location:

Milton Keynes, UK

Thursday, 29 March 2012

The Development of a Convention

At the start of the Twentieth Century, the Prime Minister, Lord Salisbury, sat in the House of Lords. By 1963 it was an accepted convention that Prime Ministers could only sit in the House of Commons. No law was ever passed; no resolution tabled in the House of Commons - the convention arose because the constitutional actors believed that it bound them.

Clearly the change in powers in the Parliament Act of 1911 altered the relative importance of each House - but there was no express suggestion in that statute about where the Prime Minister should sit. The key milestones were:-

1900 – Lord Salisbury is Prime Minister (until 1902)

1923 – Lord Curzon is considered as possible successor to Bonar Law, but Stanley Baldwin is chosen. The view was prevalent that this was because Curzon was a Peer.

1940 – Lord Halifax, though more popular within the Conservative Party, does not take over from Chamberlain, as doubts expressed about whether a Peer should be Prime Minister

1963 – Lord Home stands down as a Peer and is elected to House of Commons after becoming Prime Minister. Lord Hailsham had renounced his peerage in the hope of becoming Prime Minister.

Wednesday, 28 March 2012

One Vote!

Today is the 33rd anniversary of the confidence vote which brought down the 1974-79 Labour Government, and brought forward the 1979 General Election. For my study of whips during the 1979-2010 period it was a key event - so I have amassed much material on the events of the day.

There was confusion on the night. Jimmy Hamilton, a Labour whip had given a thumbs up sign to the Labour benches, mistakenly believing that the Government had just succeeded. However it was 311-310 for the motion of no confidence. Alfred Broughton, the MP for Batley and Morley was gravely ill - the Prime Minister, Jim Callaghan, thought it would have been inhuman to have him brought to Westminster (from Leeds - a 400 mile roundtrip) in an ambulance for his vote to be counted. He was to die a few days later.

This was one of the few examples in the 20th Century of a government defeat leading to the fall of a government. (There have been many government defeats in the House of Commons – but only three were defeats which were regarded as confidence votes - Jan 21st 1924, Oct 8th 1924 & Mar 28th 1979.

There are various accounts of that day in political memoirs; biographies and histories. An article by Roy Hattersley can be found here.

There was confusion on the night. Jimmy Hamilton, a Labour whip had given a thumbs up sign to the Labour benches, mistakenly believing that the Government had just succeeded. However it was 311-310 for the motion of no confidence. Alfred Broughton, the MP for Batley and Morley was gravely ill - the Prime Minister, Jim Callaghan, thought it would have been inhuman to have him brought to Westminster (from Leeds - a 400 mile roundtrip) in an ambulance for his vote to be counted. He was to die a few days later.

This was one of the few examples in the 20th Century of a government defeat leading to the fall of a government. (There have been many government defeats in the House of Commons – but only three were defeats which were regarded as confidence votes - Jan 21st 1924, Oct 8th 1924 & Mar 28th 1979.

There are various accounts of that day in political memoirs; biographies and histories. An article by Roy Hattersley can be found here.

Tuesday, 27 March 2012

Separation of Powers

The US Constitution is built upon the foundation of a separation of powers. Montesquieu, amongst others, had highlighted the importance of ensuring that the differing functions of legislating (making law); executing the laws (carrying out the laws and providing day to day administration) ; and judging - both interpreting the laws and deciding in invidual cases - should be in the hands of separate groups of individuals. Hence a member of Congress cannot be at the same time a member of the Executive (serving the President) or a member of the judiciary.

On the face of it, Britain seems to show a fusion, rather than a separation of powers. The doctrines of ministerial responsibility are based on the principle that Government Ministers will also be members of either the House of Commons or the House of Lords. The Lord Chancellor was for centuries a member of Parliament (almost invariably in the House of Lords); the presiding officer and major player in the Lords; a member of Cabinet and an active judge.

However - it is useful to remember that Montesquieu actually praised Britain as a shining example of 'separation of powers'. It can be fairly described as a major principle of the British system. True fusion of powers ended with the decline of absolute royal power.

The House of Commons Library have produced an excellent paper on separation of powers. It is available here. Students of UK Constitutional Law (including Open University W200 and W201 courses) will find that the process of condensing the information in this paper will assist their revision immensely.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)